"You will never feel bored..."

...

The museum is a place where we want to learn something – ideally we expect to find a walk through cultural history from beginning to date, nature sorted into categories, species and races. The Kreismuseum Syke offers us all this: horn axes from the Old Stone Age, cudges from the Middle Stone Age, a medieval tree well and a family of taylor puppets dressed in traditional costumes from 1900. A little further on we even find a big showcase displaying regional nature: herbs, rabbits, owls etc.

But then we pass a gate and it feels as if we were tumbling down a rabbit hole just like Alice – we enter a wonderland:

We have entered the world of Wire Figures, Sieves and Knüpfleri created by Mechtild Böger.

Wire Figures

It may not be an incident that we meet a rabbit here. Just like Alice who follows the White Rabbit into wonderland. White Rabbit has a watch in his waistcoat–pocket and talks, the rabbit of Mechtild Böger drives a tractor together with a dog. This motive is the first in a series of wire figures showing a tractor. It was invented when Mechtild Böger was watching a crime story on TV. She is a woman who cannot keep her fingers still. So she grapped a wire and formed the wheel of a tractor like the one that had just been shown on TV and that had fascinated her because of a very special pattern in the tyre profile. When the wheel was finished there still was a lot of wire left and so she continued until it was a complete tractor with a dog and a rabbit on top.

It is almost dogmatic for Mechtild Böger´s wire figures that she does not change the length of a piece of wire once it is cut. Thus bizarre attachments often arise: A dachshund pulling a little woman behind it, a mouse biting into a little cat’s bottom, and a partridge sitting on the hat of a hunter. But the wire is not always longer than Mechtild Böger´s idea of her image: In a mongrel of dachund and schnauzer the piece of wire forms the legs, the tail, the back and the head up to the snout – the breast is left to the imagination of the observer.

And this is exactly what makes the wire figures so special: In contrast to a pencil line that can be smudged and erased, the material resists the artist’s will to form. The wire enters into a dialogue with the artist, it has its own will, at times cooperating, at times resisting. Sometimes it is too long, sometimes it is too short. And it is very unforgiving: Once flexed it stays flexed. The wire does not forget what was done to it. Consequently it may happen that Mechtild Böger plans to form a camel and ends up with a chicken.

When I was preparing this speech I asked her how she finds the motives of her figures. Her simple answer was: "I do forms that I haven´t done for a long time." It is of course not quite as simple as that as the example of the tractor shows. Mechtild takes her motives from the images of our culture, such as TV and journals. Also art history offers her models: Does not the cavalier on the dog allude to Picasso´s minotaur? These are motives with a long cultural tradition, archetypes of our civilisation that find their way through the eyes, brain and hands of Mechtild Böger into the wire.

Sieves

Much alike and yet completely different Mechild proceeded with the sieves of which you see 608 here on the wall and more in the showcases. Here too, existing images are being formulated anew and here too, the material determinates the form of the art.

Mechtild Böger has invented the formula for her sieves herself. I would like to reveal it to you, or at least the parts that Mechtild Böger revealed to me – some little details have to stay secret, of course. Here it is: Take ordinary household sieves and abrade the ring of the basket slightly. Then take the journal "Spiegel", "Focus" or "Essen und Trinken". It has to be either of them, because of the paper quality and the printing method. Then printwith a mysterious glue method illustrations or writing on a wafer, take off the upper layer carrying the image and glue

What you can see on the wafers is – drastically spoken – a very bad, thinned out and on top of that inverted image of reality. As if Mechtild Böger was fishing with her sieves in the grey soup of reality, most of her findings vanish through the holes and she can only grab pale images. The sieves thus become symbols of our culture’s collective memory: Whatever happens is being filtered by governments, journalists, editoral offices or pure incidents before it gets into media and can enter our memory – or our oblivion. Like in a film by Hamilton a veil of harmony is been layed over the images.

It is the same with Mechtild Böger´s washed–out wafer-pictures – and that is their speciality. Beauty is good as philosophers such as Platon tell us and the wafer-pictures by Mechtild Böger are beautiful. Her motives seem elegantly put into place and the sacral image carrier wafer or host awards them an aura that is normally connected to icons.

But what we see on the pictures is no good at all: Next to a beach ball there may be found a corpse. It is not the cruel motiv but the strange arrangement of sieves that shocks us. We are used to neat systems with strict categories like those we find in books or museums. Our moral system also differs between good and bad.

Yet, Mechtild Böger puts contradictory, totally different systems of order to her auratized tableaus of sieves. It may be the colour or the form or the content that determines the sequence. Let me explain this by means of a very impressive sequence of sieves which you find on this wall here.

Next to a sieve with an erotic red lipstick there is one with the black-and-white picture of a man strung by his neck – because he has the same nice vertical line as the handle of the sieve. The sieve underneath shows two tomatoes with the same colour as the lipstick, the round form of the vegetable is in formal analogy to the heads of Helmut Schmidt and Erich Honnecker on the next sieve.

Another pair of sieves is connected by content. Next to a sieve with the ruins of the World Trade Centre hangs a sieve showing a delicious steak. What, you will ask yourself, has the most cruel in common with the most delicious? But don´t think about it, just look closely. Don´t you feel the smell of burnt flesh in your nose?

Sometimes the structure is scattered over the arrangement of sieves. The Brandenburger Tor appears again and again, but each time in a different context. It is the passage for Hitler´s Mercedes, it is the setting for marching Russian soldiers or the symbol of triumph for Gerhard Schröder who has just won the elections against Helmut Kohl.

Knüpferlis

After this arrangement shattering and confusing our categories of Good and Bad, let me turn to something more simple and blithe: Mechtild Böger´s Knüpferli. For those who did not get to know in kindergarten these rectangular little plastic grates that you can poke together I will read out what Knüpferli are. I quote from an advertisement by Dusyma the company which is producing Knüpferli since app. 50 years:

"Knüpferli are unique knottting–, poking–, binding– and building–elements

Knüpferli have been invented for Great and Small to play with

Knüpferli offer a million of possibilities [...] With

Knüpferli you will not only make technical forms, with

Knüpferli you will become creator of forms of art and nature."

And the conclusion is: "You will never feel bored with Dusyma-Knüpferli."

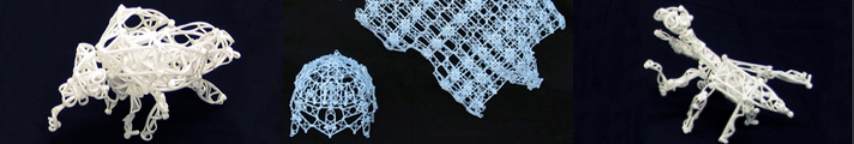

Now we konw what Mechtild Böger does in order not to feel bored. She works as a creator of forms of art and nature with Knüpferli. Her hands form bathing suits and bathing caps, mantids, sceletons of sea urchins, hunting trophies or a snout beetle. The latter she reveals frankly: “I spiked one of them when I was thirteen.” And she finally offers the systematic order that our brain was longing for in the sieve arrangements. In showcases with roman numbers from I to IV we find a differentiated scheme of order of possible Knüpferli-connections.

Accurately structured with numbers and letters we find,

Simple Knüpferli–connections,

combined simple Knüpferli–connections,

combined simple Knüpferli–connections with twisted corner,

once twisted Knüpferli–connections,

twice twisted Knüpferli–connections,

and so forth and so forth.

Point

These showcases with possible Küpferli–pictures let any scientific, nautic board of knots look like mere child´s play. Structured as this Knüpferli-system may be – in connection with the sieve arrangements it becomes evident that Mechtild Böger confronts us with a disturbing discovery. A child´s play may easily be presented in a system. Our complex cultural world with its difficult moral questions may not. Go and have a try yourself with the sieves!

[Eröffnungsrede, Kreismuseum Syke, 2004

© Daniel Schreiber, geschäftsführender Kurator der Kunsthalle Tübingen.]

Translation: Uta Schlott, Hamburg